As a travel and tourism company, we are in the business of moving around and helping people move around large distances, and as it turns out, these often take on seasonal patterns. Our locations see an ebb and flow of travellers depending on the time of the year.

Reflecting on it, we are doing something that is perhaps an ancient pattern that countless organisms have been following for tens of millions of years. Across the animal kingdom, animals not only move, but sometimes they move across large distances, and often they move across a particular circuit following seasonal rhythms.

The rest of the animal kingdom largely does this for reasons such as finding food, reproductive reasons, and finding a nicer climate… which, in a way, are somewhat idiomatic of the human reasons for tourism travel— finding food for the soul (and maybe for a change in cuisine, too!), for friendships, love, and romance, and, well, finding a nicer climate.

India also sees an ebb and flow in the organisms that live there, especially birds, as they exhibit strong migratory behaviours. In fact, 370+ species of birds migrate into India from other regions (In addition to the 920+ bird species which are permanent residents in India). These migrants originate from almost thirty countries, with the vast majority following the Central Asian Flyway. They mostly originate from Central Asia and Siberia, Northern and Eastern Europe, the Tibetan Plateau and Western China, and the Arctic regions; Africa and Southeast Asia are also notable contributors.

We see a lot of migrant birds in most of the regions we work in, and even a small glimpse reveals a stunning diversity…

If any of these interest you, just ask us in a comment or by email, and we’re happy to let you know where you might be able to see them!

All the birds that you saw just now have been spotted in the regions that we operate in. In fact, if you like birds, we highly recommend that you consider going to one beautiful property we have on our roster, near Kaziranga, which is a birding hotspot!

That said, most of our journeys and sites are great for lovers of birds and wildlife, and we are happy to have a chat with you, if you would like to know more.

A (somewhat Eurocentric) summary of the history of how humans looked at bird migrations

The interesting thing is that historically, across the world, cultures have had different responses to the fact of migrations. After all, it is indeed somewhat intriguing that some creatures should disappear altogether for some parts of the year and reappear again next year— especially considering that this is not observed in all animals, and not even all birds.

In ancient Greece, Aristotle’s ‘Historia Animalium’ (4th century BCE) provided one of the earliest systematic accounts, identifying seasonal appearances and disappearances of birds. Aristotle proposed that birds transmuted across seasons, such as redstarts transforming into robins during winter. He also suggested that some birds, like swallows, go into hibernation by burrowing into mud or hiding in crevices. Some variant of these ideas persisted well into late medieval times, at least in Europe.

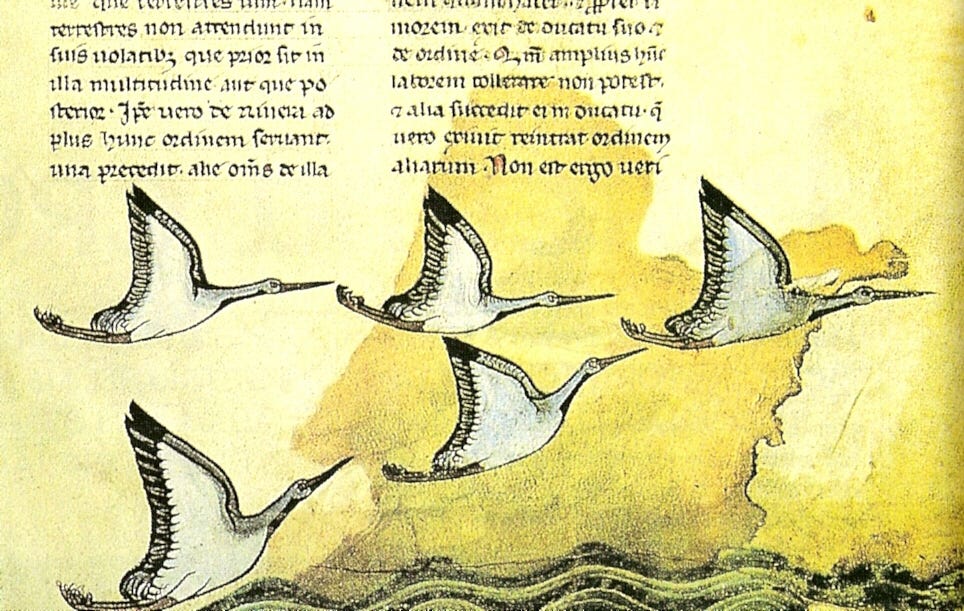

In the 12th century, Frederick II actually figured out that birds simply fly away to distant lands[1]. In fact, he was very astute in his observations:

“Birds make, as a rule, two such excursions a year, that is, from a cold climate to a warm one, and from a warm climate to a cold. The first journey to be considered—that from the cold to the warm—occurs after they are hatched and have gained their full strength and plumage. We call this their migration or passage, because they journey from cold regions, the land of their birth, to distant warm countries; the second change of residence is after the winter season and is made from warm to cold regions.”

He further lists the reasons for migrations, according to him, such as:

Chiefly to avoid excessively cold or very hot weather

Their search for food

Predatory birds migrate following their prey

While this is a simplified view, the alignment with modern understandings of migrations is quite strong. But many people at that time felt that it was ridiculous to imagine that birds might be able to fly such long distances, such as between countries or continents. So they chose to believe the far more reasonable explanation, which is that birds turn into mice during winter. To the casual viewer at the time, this belief might have emerged from the misinterpretation of the observed data— during the winter season, the number of birds seen outside reduces while the number of mice coming into homes increases.

In the same text, Frederick II also challenged myths around some migratory birds like the Barnacle Goose. Since there was no clarity about where they came from or went, it was believed that they grew from barnacles and/or in the form of fruits growing from a tree. However, he was not successful in changing people’s beliefs.

What is remarkable is that even five centuries later, there were, let’s say… unusual ideas… to account for the seasonal disappearance of birds. People still believed that birds hibernated inside mud, or in swamps, or in frozen lakes. Such ideas were not unchallenged, though. In the 17th century, for example, Charles Morton, a scientist whose writings were used as important texts for teaching science at both Harvard and Yale, pointed out that it would be unlikely that birds hibernated under mud, because it would be too cold and they would have no air supply. Moreover, he did search for evidence to support the idea of hibernation but found none in England or indeed all of Europe. Hence, he suggested, it was obvious that the birds migrated… to the moon, at the speed of 201 kilometres per hour (125 miles per hour, as he calculated).

This is, of course, a reasonable inference— after all, as we all intuitively know, there are only two possible places that birds can go in winter. If not under the mud in Europe, then “…whither should these creatures go, unless it were to the moon?”, Morton ruminates in his writings[2]. As a reference to how our scientific understandings change and technological achievements progress, consider this: about 300 years before this sentence was penned down, the dominant belief was that the Earth was at the centre of the universe, and within about 300 years after this sentence was penned down, man had already set foot on the moon.

[1] De arte venandi cum avibus

[2] An Enquiry Into The Physical And Literal Sense Of That Scripture Jeremiah Viii.7

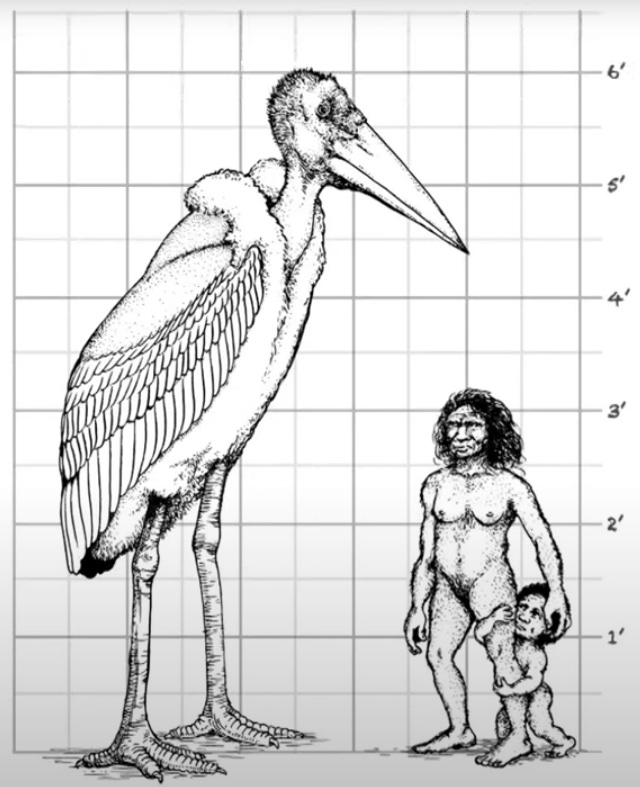

It was only after another two centuries that material evidence was found that confirmed that after leaving Europe, birds did in fact migrate to other continents on Earth itself (shocking, we know). In 1822, near the German village of Klutz, a white stork was found with a 30-inch-long spear going through its body and neck. This spear was made of African wood. Thus, it implied that this bird must have gone to Africa, which was about 3,200 kilometres away, before returning to the German coast.

By the 1880s, migrations of birds found their way into popular literature as a matter of fact. For example, Oscar Wilde’s well-known fairy tale ‘The Happy Prince’ depends on the migration of swallows as a core plot element.

Interestingly, the idea that birds go to Africa was not a new one. More than 2000 years ago, the Greeks deeply believed that there was an ongoing geranomachy, that is, a terrible, fierce, and endless conflict between cranes and a diminutive race of people known to them as the pygmies. The pygmies were thought to exist at some remote place, which was sometimes identified as India or Africa. The name for the so-called ‘pygmy peoples’ comes from this story. In this regard, there is a reference to the migratory behaviour of the cranes, seasonally going back and forth between two places. As found in ‘Historia Animalium’ by Aristotle (4th century BCE): “these birds [the cranes] migrate from the steppes of Scythia to the marshlands south of Egypt where the Nile has its source. And it is here, by the way, that they are said to fight with the pygmies; and the story is not fabulous, but there is in reality a race of dwarfish men, and the horses are little in proportion, and the men live in caves underground.” The Iliad, which is typically dated to the 8th century BCE, also refers to this conflict to draw a parallel in the Trojan war.

In fact, references to this conflict can be found in European, Arab, Chinese, Japanese, African, and even Native North American sources.

While there are mythic explanations for this conflict, Pliny the Elder made a more sober assessment in ‘Naturalis Historia’ (1st century CE): “This tribe [the Pygmies] Homer has also recorded as being beset by cranes. It is reported that in springtime their entire band, mounted on the backs of rams and she-goats and armed with arrows, goes in a body down to the sea and eats the cranes’ eggs and chickens, and that this outing occupies three months; and that otherwise they could not protect themselves against the flocks of cranes would grow up; and that their houses are made of mud and feathers and egg-shells.”

Incidentally, according to some researchers, current evidence is beginning to hint that the geranomachy may in fact be not just a myth but a racial memory of a very real conflict[3] between diminutive humans and large cranes, storks, and similar birds— and the basis of this conflict may have been rooted in the birds migrating to some places to lay eggs, and the pygmies then raiding the nesting sites to gather those eggs. According to this hypothesis, the descendants of these pygmies are in fact the various pygmy peoples who are extant (and who, incidentally, are the largest group of hunter-gatherers in today’s world).

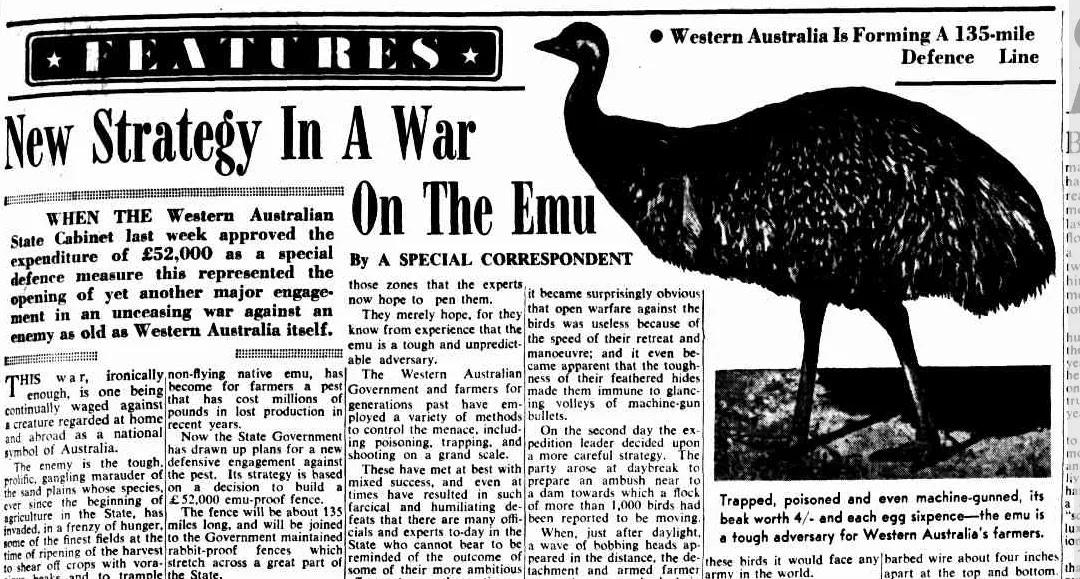

If this turns out to be true, this would be one of the earliest, most widespread, and very vivid threads that highlight the human memory of migrating birds. Should we ever take the war between cranes and pygmies lightly, let us not forget that we humans lost the Great Emu War of 1932, despite deploying soldiers of the Royal Australian Artillery, armed with machine guns and thousands of rounds of ammunition.

As was reported at the time, “The emus have proved that they are not so stupid as they are usually considered to be. Each mob has its leader, always an enormous black plumed bird, standing fully six feet high, who keeps watch while his fellows busy themselves with the wheat. At the first suspicious sign, he gives the signal and dozens of heads stretch out of the crop. A few birds will take fright, starting a headlong stampede for the scrub, the leader always remaining until his followers have reached safety.”

[3] A quick summary by Jared Cooney Horvath.

[4] Report by The Canberra Times

So, despite such observations by Homer, Pliny, and Frederick II, who lived hundreds of years apart from each other, why did the hibernation of birds become accepted as a fact as late as the 1800s? Why could Aristotle himself, who in the same book writes about the flight of the cranes, go on to suggest that birds in fact hibernate or transmute, rather than making the connection that maybe, like the cranes, other birds fly away as well? There’s no one pithy answer. Scientific study and democratic agreement both take time, and this is no exception.

What about the connection between bird migrations and Indian culture?

Yes, there are references to migrating birds in India since ancient times[5].

Hymns of the Rigveda, which are typically considered to be the oldest extant Hindu texts (c. 1500 BCE), Hindu epics such as the Mahabharata, the Ramayana, and later Hindu texts have references to the hamsa and various birds with the root suffix ‘hamsa’. The hamsa is an aquatic, possibly migratory, bird that is variously understood to be a goose, swan, or even a flamingo, and the birds which have ‘hamsa’ in their name are identified as various waterbirds, typically swans, ducks, and geese. The hamsa and the paramahamsa serve an important symbolic role, thought to depict the transmigrating soul and the supreme soul of the universe, respectively. The term ‘Paramahamsa’ is used as an honorific for highly attained Hindu sadhakas. The hamsa is also considered to be the vahana of major deities like Saraswati and Brahma. Indeed, there are two Upanishads called the ‘Hamsa Upanishad’ and the ‘Paramahamsa Upanishad’.

The well-known ornithologist Salim Ali (the ‘Birdman of India’) spoke about the hamsa birds mentioned by Kalidasa (c. 4th or 5th century CE). In his Azad Memorial Lecture for the Indian Council for Cultural Relations, Ali said, “Classical Sanskrit literature occasionally makes specific mention of Bird Migration, as for example the migration of geese (hamsa) — wrongly rendered as ‘swans’ by many commentators — to lake Manasa (Manasarovar). The poet Kalidasa, a close observer of bird behaviour— described the migratory habits of two species of geese, Raja-hamsa (Barheaded) and Kadamba (Greylag) as accompanying the rain clouds on their way from the Vindhyas to the Himalayas.”

In Tamil Sangam literature, typically dated to the turn of the Common Era, there are references to bird migration. For example, the ancient Tamil poets noted that the migratory white storks arrived from outside the region and returned seasonally; hence, in the compilations like Akananuru (verses 100 and 190) and Kurunthogai (verse 236), they are referred to as vamba naarai (‘Guest birds’)[6]. The poet Paranar in the of the Natrinai describes beautiful swans that live in the Himalayas[7]. Sattimurram Pulavar’s famous poem about the stork also describes bird migration[8]. In the 67th song of Purananuru, there is a reference to a bird travelling to the North after feeding on ayirai fish in Tamil Nadu[9].

[5] Krauncha and Sarasa in Sanskrit Literature

[6] Article by M. Amirthalingam

[7] Verse 356 of the Natrinai

[8] Sattimurram Pulavar’s poem

[9] Sangam Translations by Vaidehi

Extant festivals like Saama Chakeba celebrate bird migrations. Saama Chakeba commences when birds begin to migrate from the Himalayas to the plains of India. It most likely originated in the Mithila region and is celebrated by the Maithil and Tharu people as a festival of unity, love, and the bond between siblings.

One key aspect of this festival is that people make clay or papier mache bird idols as a tribute to the legendary Saama, who had been transformed into a bird, and in reality, as a tribute to these migratory birds.

Sometimes, even ancient ideas have modern impacts. For example, the Jain beliefs of non-violence and care for all creatures have taken an interesting shape at a small town named Khichan (‘City of Cranes’) in Rajasthan.

A lot of the villagers are Jains, and they feed the Demoiselle cranes with grain as the birds migrate further south. It is an amazing sight, and now a well-respected ritual. Apparently, this started as recently as four decades ago with a few hundred birds. Now, around 25,000 cranes visit the village annually, and it also attracts tourists. While all human-animal interactions can have unexpected consequences, we are cautiously optimistic about this story.

But how do birds manage to migrate over thousands of kilometres, back and forth, without GPS or even a mobile?

That is a story for another day, but current research shows that, amongst other things, certain quantum physical phenomena may play a crucial role in the process! For a long time, there has been a hypothesis that birds sense the Earth’s magnetic field and use that data to find their way across the planet. So how do the birds actually sense the fields? The data increasingly support the idea that chemicals called cryptochromes in the birds’ eyes help sense minor fluctuations in the Earth’s magnetic field using quantum mechanisms[10]. There is, in fact, a significant difference between the magnetic sensitivity in the chemicals in migratory and non-migratory birds. Moreover, earlier research suggests that birds process magnetic data in the visual centres of their brains. Hence, this has led some researchers to suggest that birds may be able to ‘see’ the Earth’s magnetic field[11].

[10] A summarising look by Jim Al-Khalili.

[11] A summary by Nature video.

NB: The images for the newsletter have been gathered from various sources on the internet, and we are sharing these photos in the spirit of fair use. As much as possible, we sought out images which were in the public domain and/or under Creative Commons licences.

You can read the previous versions here: